Sketching in Hardware 2025 @ Paris Fr.

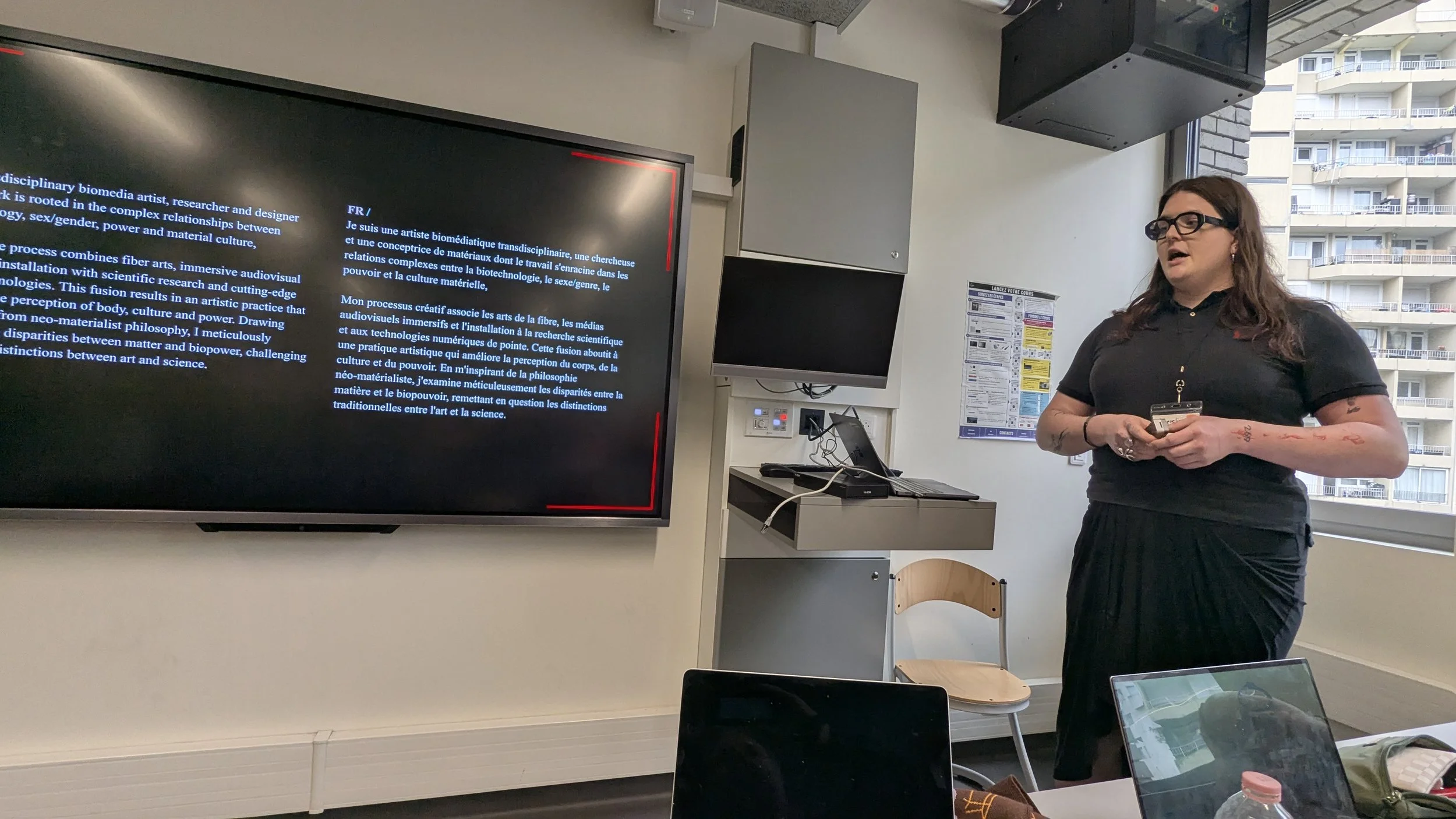

During my presentation at Sketching in Hardware, I talked about my practice as a biomedia artist and MA student at Concordia University. My practice has always lived at the intersection of the tangible and the microscopic—I work in fiber practices, transforming genetics into textile objects you can touch, see, and experience in physical space. Over the past few years, I've been working with genetic material in unexpected ways. I've taken the genomes of H1N1 bird flu and swine flu and translated them into fiber projects. Using a digital jacquard loom, I've woven a series of tapestries that visualize the genetic sequences of various organisms—HIV, honey bees, COVID-19, cuttlefish, and others. When you look at these tapestries, they appear almost like television white noise or incredibly complex QR codes, patterns that hold within them the literal building blocks of life.

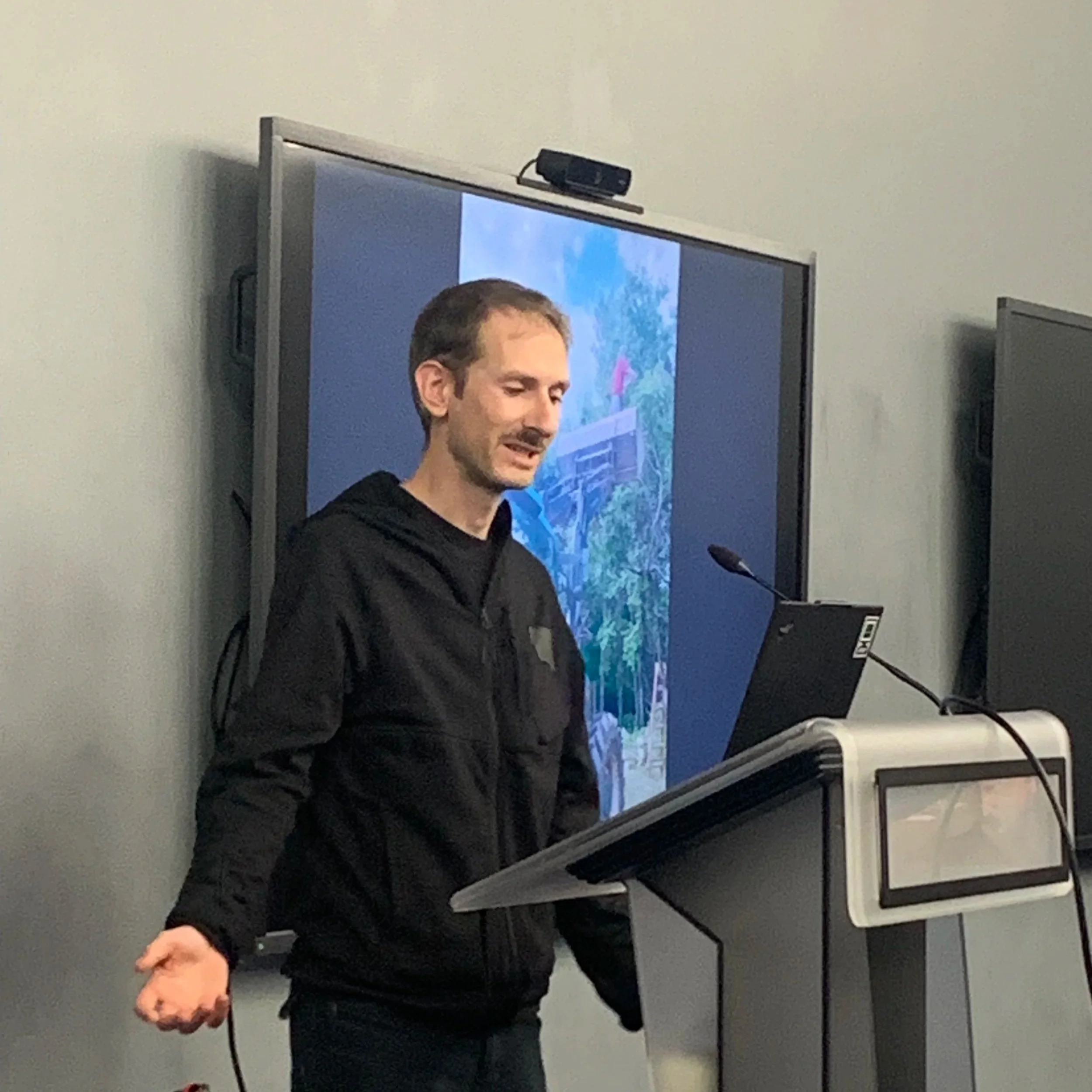

My current project, Wet Dreams, takes this exploration of invisible biological material into an entirely new realm. Instead of working with isolated genomes, I'm DNA-analyzing the collective breath of dancers on a dance floor, capturing something ephemeral and intimate—the microbiome we exhale and share in moments of physical expression and community. The inspiration comes from Mariko Mori's Wave UFO installation, which used EMG readings to create audiovisual visualizations projected onto a dome, François-Joseph Lapointe's Holy Microbiome, which examined bacteria at religious pilgrimage sites, and Edit Architecture Collective's D.A.M.P., which collected excess water from air conditioning units and created moments where inhabitants could encounter it. Technically, I'm using a MinION Portable Genetic Sequencer—a palm-sized device that can analyze DNA in as little as 45 minutes, the same technology used on the International Space Station. A dehumidifier collects the moisture and microbiome genetic information from the dance floor environment. The MinION software outputs a text file that feeds directly into TouchDesigner, which I've programmed to transform the DNA sequences into four-channel visualizations. In this way, Wet Dreams makes visible the invisible ecosystem we create together when we dance, breathe, and share space—turning the poetry of collective biology into light, pattern, and presence.

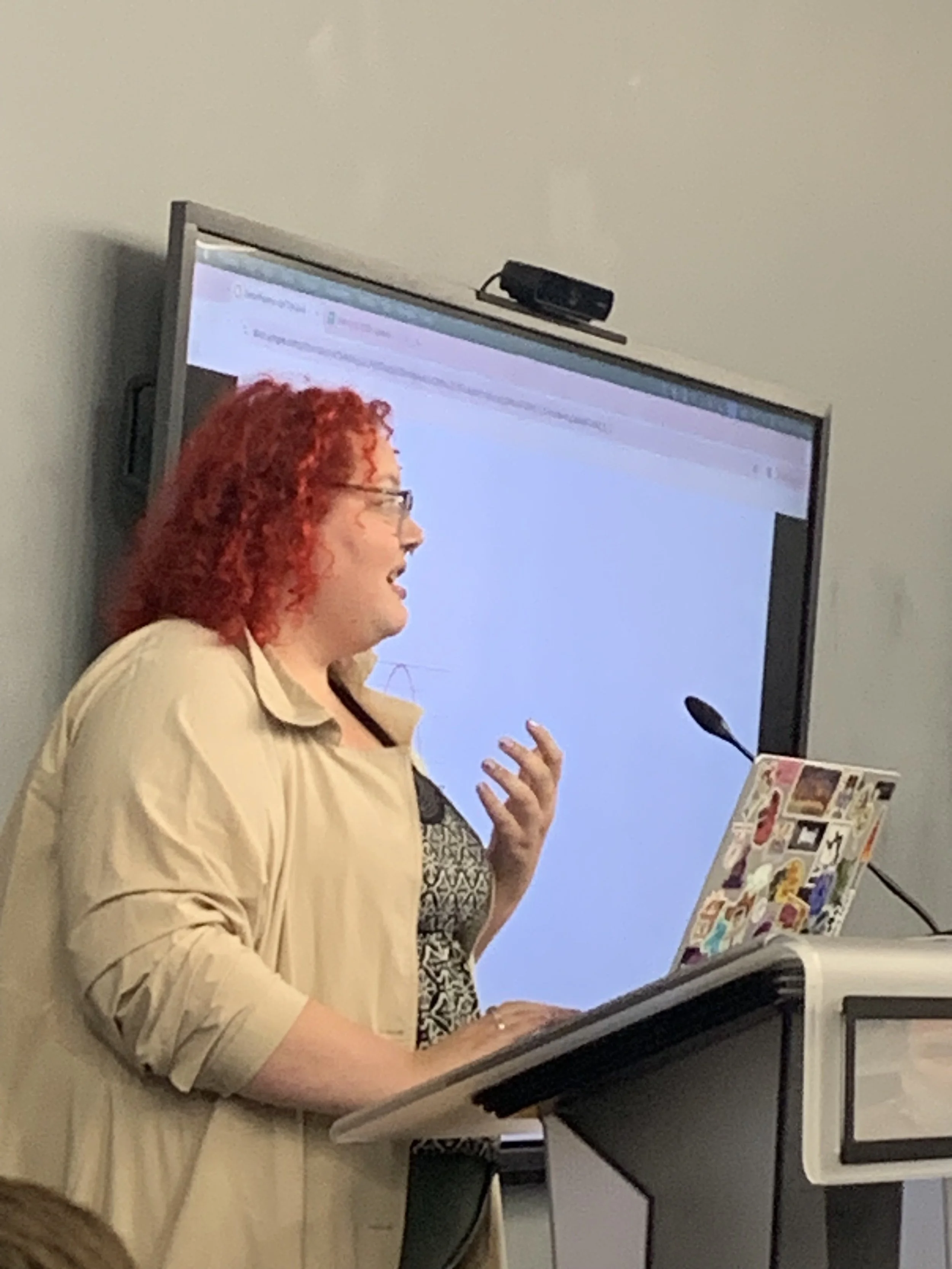

Ashley Jane Lewis: a new media and bioartist and ITP alumna, explores slime molds in relation to Black culture, asking what techniques cultures use to survive and flourish. Her work often employs quick DIY hacks to measure bioculture behavior, and she's built a mobile Slime Tech Lab that she rolls into Black neighborhoods to explore what happens when communities collaborate to care for organisms while engaging in difficult conversations. She previously presented this work at Sketching in Hardware in 2019 and 2023. Her research draws fascinating parallels—between maps of the internet and the Underground Railroad that helped African Americans escape slavery, and between mycelial networks (the "wood-wide web") and contemporary connectivity. As Shaina Agbayani wrote, "It is not to dust that we return, but to bacteria"—a sentiment that resonates through Ashley's exploration of interdependence and survival strategies across species and time. Her work taps into the current cultural fascination with mycelium while centering often-overlooked perspectives on resilience and care.

Yeseul Song: who teaches Physical Computing with Tom Igoe at ITP, presented her portfolio in an unexpectedly delightful format—a spreadsheet, the first such presentation I've witnessed at Sketching in Hardware. Through a series of projects, she traced how "physical" and "computing" have played out and transformed in her work over time: beginning with systems responding to bodies through computation, evolving into bodies responding to each other with computational assistance, and ultimately arriving at bodies working together, connected physically and amplified with computation. A key insight from Yeseul's work is the concept of "warming down" and "sensory adaptation/calibration" that happens when experiencing her pieces—a process necessary to adopt unfamiliar sensory languages and become able to truly feel and perceive. Her current work unpacks figure skating's unique sonic nature through a new performance piece. You can explore more at yeseul.com or follow her @yeseulsong

Maxime Damecour: reframed "profit" as enjoying your work without burnout. He demonstrated a $30 laser figure maker with impressive mechanical engineering, controlled using audio technology. In a clever hack, he made his own PVC plates by slicing and flattening PVC pipes in a well-ventilated area. His approach leverages the fact that every computer has an audio jack, enabling physical computing through audio frequencies and their interactions—no specialized hardware required. He designed his audio sculpture to fit into an airline-baggage-compatible road case for easy transport. Though initially resistant to working with video, he discovered Processing and hasn't looked back. He's also developed LED drivers on microcontrollers and concluded with an awesome live coding demo that brought his vertical integration philosophy

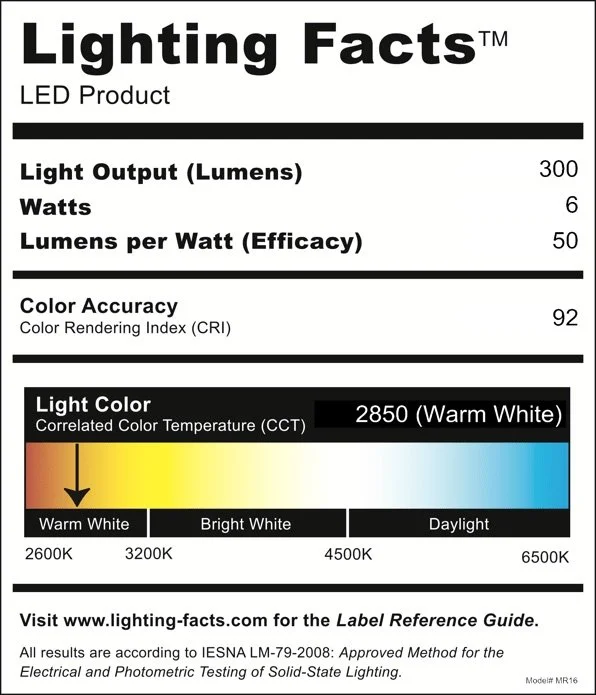

Paloma Fautley: now at span.io, began her talk by admitting she knew little beyond the basics about the power grid. She explained that even the US has several separate grids, with Texas operating its own independent system. Grid frequency deviations of more than 0.2 Hz can tear transformers apart due to magnetic coupling—a phenomenon that contributed to a major outage during a seven-day storm in Texas. Because Texas wasn't connected to other US grids, no one could help. (Kipp Bradford fact-checked this, noting that the Texas grid is tied to the rest of the US through high-voltage DC interconnects totaling about 1200MW, but they refuse to frequency-lock, which is why the interconnects are DC—and insufficient for emergencies.) Domestic electrical energy use in the US is expected to double by 2028, making grid resilience increasingly critical. Paloma referenced Saul Griffith's book Electrify: An Optimist's Playbook for Our Clean Energy Future, which argues that we need to electrify our appliances, vehicles, and buildings, then network them all to balance loads and create a more robust, resilient grid that provides lower energy costs for everyone.

Sophi Kravitz: is creating an art installation that uses cosmic rays to trigger audio stories about possible futures—a work in progress that will continue evolving over the coming months. Her goal is to translate something invisible into something meaningful. Cosmic rays, she explained, are actually particles from dramatic events in space, not rays at all. She built her first cosmic ray detector in 2010 for Burning Man, using Geiger-Müller tubes that cost $300 each at vintage surplus stores. For her new project requiring a large supply, she sourced them from Jeff Keyzer, who makes ray detector circuits. She discovered that using JLCPCB for both work and art projects was transformative, and keeps a ChatGPT window open to help with KiCad and similar tools. Rather than contributing to the doomsday narratives prevalent in current news, Sophi wanted to ask: where's the joy? Her audio stories imagine optimistic futures, like 3D-printed hip replacements in the comfort of your own home. She cited Cloudflare's lava lamp array that creates random numbers for encryption keys as related work, envisioning her installation as "experiencing a random field of optimism." She vibe-coded the entire thing, initially using text-to-speech for prototyping but now collaborating with two sound designers for human voice recordings. Find her @sophikravitz on social media or at sophikravitz@gmail.com.

photo credit to Mike Kuniavsky

Eldy S. Lázaro Vásquez: shared her journey working with materials that transform and decay. Having successfully defended her PhD following her MSc at UC Davis, Eldy brought a perspective shaped by her roots in Peru's Fab Lab community and her move to the United States, where she's been asking a central question: How can we incorporate sustainable design practices into maker and research spaces? Her approach centers on modular design, design for disassembly, and biomaterials. She began by embedding electronics into mycelium, presenting wearable myco-accessories at ISWC/Ubicomp 2019 that earned a design award. By Ubicomp'23, she had moved into dissolvable wearables and garments designed to unfold over time. To scale up production of her biofibers, she spent the summer of 2022 working at the Institut für Textiltechnik (ITA) at RWTH Aachen University in Germany, which resulted in an open-source machine for desktop biofiber spinning. For Eldy, biomaterials are the tangible manifestation of her biggest interests: a design practice that honors life cycles, interdependence, and transformation. She's explored various affordances of biofoam, including its opacity and capacity as a color carrier. Her latest project investigates bioplastics that shape-change with humidity through swelling rather than dissolving, continuing her exploration of materials that respond to their environment and evolve over time. You can learn more about her work at eldylazaro.com

The Desktop Biofibers Spinning Machine is an open-source, modular machine for producing textile fibers from sustainable bio-based liquid solutions. It enables prototyping new types of sustainable fibers and exploring the design of sustainable smart textiles. It supports spinning fibers from bio-based solutions, including ones that require heat during the spinning process. This repository contains all the design-related details and files to build the machine.

Zach Fredin: opened with a provocative image: the "heap of shame"—all the waste wheeled out after a fabrication workshop. His mission is to "sketch-to-machine all the things," but he's grappling with the environmental cost. He loves his waterjet cutter but confronts the reality that it uses one pound of granite powder (garnet) per minute, producing a pound of garnet sludge every minute of operation. His radical question: Could we charge for waste produced instead of material used? Before buying the machine, how does it fill the dumpster? In response, he prototyped a variety of materials that repurpose the waste into ceramic composites, and he gifted the audience fired hexagon buttons with our initials—a beautiful demonstration of closing the loop. Currently based in Kingston, New York, you can explore his sludge-craft project at zachfred.in/projects/sludge-craft.

references i found along the way

The Radium Girls were female factory workers who contracted radiation poisoning from painting watch dials with self-luminous paint.